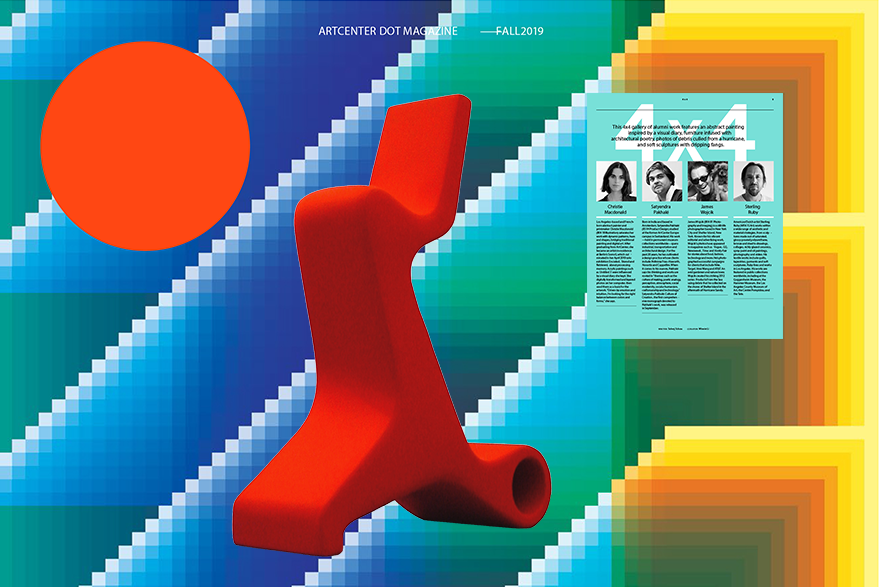

Dot Magazine – Art Center College of Design features Pakhalé’s pieces infused with architectural poetry in 4×4 alumni: Satyendra Pakhalé, Christie Mcdonald, James Wojcik and Sterling Ruby, wrote by Solvej Schou.

Amsterdam-based designer Satyendra Pakhalé, whose sensory-sparking and sinuous work—held in museum collections worldwide—spans industrial, transportation and architectural design, grew up in India loving drawing, painting, physics and mechanics.

Encouragement from his socially conscious teacher parents pushed him to be a maker at an early age. He was also inspired by the Ajanta Buddhist caves, paintings and rock-cut architecture—dating back to the second century B.C.—in the Maharashtra region where he was raised.

“When I was growing up in India, things were not industrially made, so you made your own,” he says. “You didn’t go to a toy store to buy a toy. You would pick up wood, go to a carpenter and make toys for yourself. You make what you can imagine. That’s exactly what I do today, except with somewhat better abilities.”

After discovering a book in his school library by the modernist American designer George Nelson, and reading it cover-to-cover, Pakhalé decided to pursue design. He earned a degree from the Industrial Design Centre (IDC) at the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT Bombay). When he expressed to his mother the wish to study abroad, she spoke to family friend and Southern California native Dr. Orpha Speicher, who founded a missionary hospital in his hometown. She told Pakhalé’s mom about ArtCenter, and brought back a brochure from a summer trip.

Pakhalé reached out to ArtCenter and was offered scholarships to study at the former ArtCenter Europe campus in Switzerland. “Going abroad from India at the time was not easy for various reasons, including foreign exchange limits,” he says. At ArtCenter Europe, Pakhalé was taught a variety of design thinking methods by “wonderful minds,” he says, from designer Wolfgang Joensson to Simon Fraser, who worked then at Porsche Design.

After graduating, Pakhalé worked at Frog Design and Philips Design. At the latter, his projects included working on the Pangéa, a 1997 concept car developed for French car company Renault and designed for use by environmental researchers. After leaving Philips, he started his own design practice in Amsterdam in 1998, where his clients include Poltrona Frau–Haworth, Novartis and Cappellini.

“I was eager to explore all sectors of design, from handmade to machine-made and in-between,” he says. When it comes to his oeuvre, Pakhalé says his work is rooted in the culture of making and themes of poetic analogy, perception, atmosphere, social modernity, secular humanism, craftsmanship and technology. “I aim to create sensorial qualities in industrial design, such as the texture and warmth we recognize in age-old objects, yet without passively accepting traditions,” Pakhalé says. “The sensorial experience is essential.”

For instance, his 2002 multi-chair Panther, with its iconographic swooping lines and curves, was designed to celebrate the golden jubilee of Italian furniture company Moroso, and combines three sitting positions in a single form, evoking a leaping panther. “I created it to entice the user to try out various postures: sitting, lounging, reclining,” he says. “Panther is intended to make us aware of our existence and to take time for contemplation and deep breathing.” His 2001 Flower Offering Chair is a chair-like ceramics piece, structurally strong enough to sit on, with two removable vases in its backrest to hold flowers.

Satyendra Pakhalé: Culture of Creation, the first comprehensive monograph devoted to Pakhalé’s work, was released in September 2019 as a “labor of love,” he says. It includes images of his work and 12 critical essays by a range of designers and thinkers, including architect Juhani Pallasmaa, Museum of Modern Art Senior Curator of Architecture and Design Paola Antonelli, and former Philips Design Chief Executive Officer Stefano Marzano.

“Each project we work on goes through rigor and lots of care, and we stand behind each piece that we bring into the world,” Pakhalé says. “The monograph speaks about that journey.”