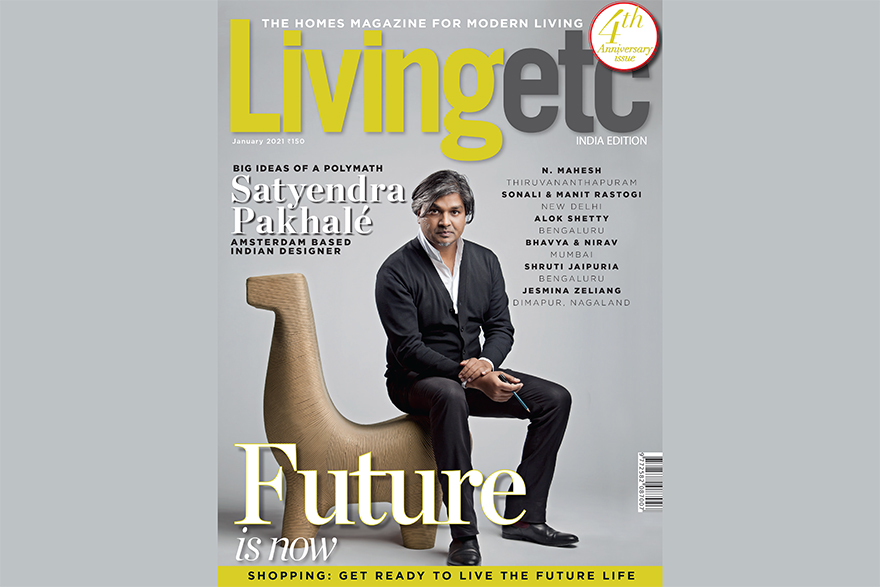

Mr. Satyendra Pakhalé interviewed by Mrs. Mridula Sharma

For Living Etc Magazine, India / Anniversary Issue / January 2021

Mridula Sharma / MS: As a child, did you ever have a vision of yourself, as the designer of stature that you are today?

Satyendra Pakhalé / SP: Being a curious child and always fascinated and interested in creating, drawing, making things and also engrossed in sciences – particularly physics and mathematics, I would say yes. From early on I felt a need to create. This was recognized, encouraged and supported by my parents, they seemed to have an intuitive understanding of creativity and nourished it. The journey has been from one curiosity leading to the next. Early on, I felt I needed to work internationally and work with the best of the leagues.

MS: It is lovely to see how you have integrated the Dokra form into your BM Horse design.

What made you choose that particular craft?

SP: Often industrial design products, with their built-in obsolescence, lack ‘symbolic content and cultural significance.’ In an attempt to find alternatives to this sterility in mass manufactured goods, I wanted to create ‘sensorial qualities in industrial design – such as the texture and warmth we recognize in age-old objects, yet without passively accepting traditions. As a means of reclaiming sensoriality, I saw with a fresh perspective a technique that has been practiced for many hundreds of years in India: the art of cire perdue – lost wax metal casting. Once ubiquitous, the ancient craft is still practiced in bell metal by the Muria community in the Bastar region of central India, also called ‘Dokra’. During my first trip to this area in the early 1990’s, I was captivated by the Muria people and their ancient yet progressive way of living. Their process of making lost-wax cast objects is completely pre-industrial and is rooted in their way of living. The Muria are one of India’s oldest indigenous people. I was fascinated by their democratic social structure and the dance-loving socio-ethical educational system of Ghotul: a training resource centre and recreational club for young people based on equity, simplicity and freedom. The culture of object- making is at the heart of their way of life.

However we have made a basic principle to avoid ‘the codified forms and style of traditional craftsmanship’, nevertheless, I have always observed traditional cultures objectively, reflecting on their meaning and relevance in the contemporary context. My objective is always to create contemporary works with universal reach and the sensorial qualities that I value so deeply. The Muria craft techniques that I discovered offered the perfect opportunity to do exactly that. Working together with Muria craftsmen, my early experiments evolved into the first generation of Bell Metal objects and that curiosity led to giving birth to an idea that became B.M. Horse. Though it took seven years of experimentation to make it the seamless piece I had envisioned.

Three periods of lost-wax casting experimentation in bell metal can be identified in my studio practice. Spanning over fifteen years, these early experiments resulted into the family of the first, second and third generations of the B.M. Objects. Each generation has its own distinct identity. They are differentiated not only by the objects’ sizes, proportions and formal language, but also the object-making process and technique that evolved with each generation of B.M. Objects.

MS: What according to you are going to be must-have wearable tech accessories for us. (ref wearable air quality badges)

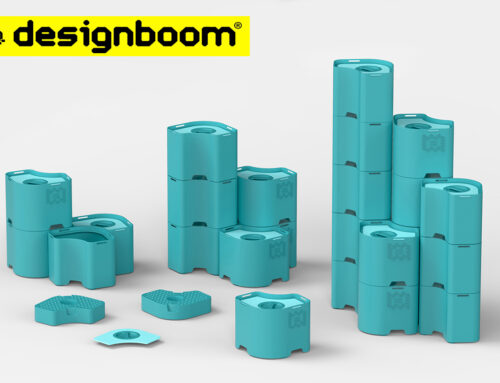

SP: The topic of wearable technology has been dear to me for a long while. I have been engaged with it since the early 1990’s since Art Center Europe times in Switzerland. Although having created and envisioned many ideas, concepts which one could say were ahead of its times, there is still plenty of work to be done in the sector of healthcare and wearables. Such objects ought to be seen as a part of individual personality just like one wears a watch or a spectacles and not perceived as a handicap or even worst – perceived as a chronically ill person, let’s say, like in the case of a diabetic person. Most of the wearables so far are not designed from this perspective; they are often clumsy technical-looking devices.

I think in a broad sense wearables that assist us, monitor health and our conditions are really needed especially for people with chronic conditions which – if designed with a refreshing perspective could also become recreational. This requires real leap in imagination to envision and create such possibilities and we are working in that direction.

MS: What are some of the typical things that we follow as Indians, must we, in your opinion; continue to do so. eg. our use of spices and turmeric which has stood in good stead during the pandemic.

SP: There is a long Indian heritage, with knowhow and ways of sensorial living that we have cultivated over a significant period of time. It needs to be tapped in a manner without succumbing to nostalgia, false narratives or traditionalism. Turmeric is one such example, but if one searches deeper one finds wonderful lessons in architecture from natural ventilation to planning. There are many archaeological sites littered all over India from Nalanda in the north to Amravati in the south with so many typical things that need to be studied with a refreshing perspective. Unfortunately modernity arrived in India just as a visual modernity. In my view the project of ‘modernity’ is still a work in progress in most of the societies around the world let alone in India, to achieve diverse, equitable and inclusive social cohesion. There is still a way to go for all of us; it has become evident during this pandemic. One of the critical issues is developing a dynamic relationship with historicity. I have always felt we cannot create the future, if we do not understand the past.

Having said that, India abounds with people’s knowledge and innovative ideas. Indeed much of what we think as uniquely Indian has come to all Indians not through reading and writing, but through the wordless sensorial way of life. This evolved from tactile, visual and sensorial enthusiasm. The range and diversity of Indian manual and culinary crafts are staggering. However if they are not cherished, refreshingly up-dated and integrated in our contemporary way of life by cultivating a true sense of modernity, it will all disappear. India is a society in process; design is still defining itself. In today’s information society and beyond the sensorial approach to Indian way of life has a lot to offer to the world through design.

MS: If you were asked to pick one utensil/cooking vessel from an Indian kitchen to re-design, which one would it be? and why?

SP: It is always harder to pick one, in fact there are many kitchen utensils seen from the cultural condition that need to be rethought to fit our current needs with new applications of materials, manufacturing and usability. Looking at the panorama of cooking utensils from India, there is a lot to choose from. But the one that obviously comes to my mind now is to design a new multipurpose pan which will have health benefits and will be suitable for cooking multiple dishes using aerospace grade materials. We have the technology in India, it only needs to be made.

But thinking of the Indian kitchen I have already rethought a steam cooking utensil from Kerala called ‘puttu’, it has vertical proportions and is traditionally made of bamboo. Taking the basic idea of steam cooking, we developed it into a contemporary vessel for preparing wholesome food. I wanted to evoke the notion of the good-old ‘square meal’ and what it means to us today.

Another recent example is NEKA® — non-electric kitchen appliances, a collection that revisits traditional hand-operated cooking objects that were so often used in a traditional Indian kitchen. NEKA applies recent developments in materials and manufacturing techniques and offers a sensorial and efficient way of preparing food, with minimum components that are easy to clean. The human effort required to use NEKA objects is significantly less than that needed for traditional hand-operated kitchen appliances. The set comprises a blender, a mixer and a whisker that evoke a sculptural aesthetic while still being functional. The challenge of this project was not only to innovate the working mechanism on the NEKA objects — both technically and poetically — but above all, how wider masses could accept slow cooking and doing things manually, but somewhat ironically, now as we go through the COVID-19 crisis, such ideas are being taken more seriously, understanding the innate values of aware living.

Akshat Bhatt/ AB: Your work seems to draw on a myriad of references. Tell us about them. Satyendra Pakhalé / SP: Intellectual curiosity has been a constant feature of our design practice, leading to various themes and projects that provide a wider, deeper context and cultural connections across the works. With our engagement with a wide range of topics cultivated over the years I see the world as one place of our common human condition. The ‘Culture of Creation’ is the thinking and the research that inspires our everyday studio activity. It aims at exploring why we as human beings do what we do and how the things we create nurture our sensorial and social nature. Each work gives us the possibility to contextualize our multi-facetted, culturally diverse and technologically rigorous design practice, sheds light on our design approach, way of creation, studio practice itself along with a critical thinking, world view and intellectual position.

AB: Your academic foundation was in mechanical engineering from a college in India. But you practice design and your studio is truly a global one based in Europe. How did you manage the transition?

SP: It has been continuity, not a transition really; there was always a keen interest in creating and making things. It started early on during childhood and was encouraged early on leading to continuity of creation. So called academic foundation has never been a limitation or sole defining condition. In that sense I really never decided to become a designer or an architect; it was just a natural progression. But in terms of discovering the profession, there was a kind of beginning. I found a tiny book by Architect George Nelson in one of the school libraries. I was sitting in the middle of India and I read that whole book and decided that was something I wanted to pursue for the rest of my life.

AB: How closely does your work reflect your theoretical position?

SP: The so-called theoretical position is a way of thinking, the manner in which it triggers one’s mind, with which it creates possibilities to be manifested and associations to be created. But eventually it all depends on the awareness and perception of the people, the end users or shall we say audience that is the subject. Accordingly what the viewer can or cannot see or experience all depends on their personal awareness and cultivated senses. So some people may directly experience, see and relate to the associations whilst others will not.

Objects and spaces do not have awareness – but, they have the innate power to evoke awareness within us. Each object and space we surround ourselves with, represents our aspirations, hopes, and desires. Above all, objects evoke sensorial response. For me, objects and spaces are like companions, symbols that enhance our human- made world. Objects and their environments we create can provide us with much more than their mundane utility. I am fascinated by how objects, spaces and their atmospheres have the potential to recharge our life settings with meanings and sensorial qualities. In a sense, objects enhance our embodied relation with the world. Fundamentally, objects support and celebrate our day-to-day lives and give us a sense of dignity. For me, a holistically designed object and space ought to take all human needs into consideration; encompassing the whole body, intellect and all bodily senses including the ‘sense of mind’.

AB: I’m curious about ‘the culture of creation’ and this diversity of your work; some have definitely crafted roots while others have a firm bias towards engineering and production. You negotiate the two effortlessly. Some of your work is distinctly one or the other, but talk about the projects where one takes over the other.

SP: I do not see the act of creation in a fragmented manner, it is always an act of unity, where very many facets are synthesized, in each work there is aim for that unity or shall we say oneness. In some works – one facet manifests itself more than the other, depending on the context and the given condition. But we don’t perceive them in a separate or stratified manner.

Every project that captures my imagination is equally important. There is simply no hierarchy. I am as much interested in designing an object to a complex multifaceted technological product such as medical device. Interested in creating private architecture for a nucleus family to creating muti-layered public architecture.

As human beings we are constantly immersed in different atmospheres and spontaneously associate them with space. In over more than two decades of experimentation, we have developed a research program complementary to studio practice. While designing objects and spaces we investigate their related atmospheres and cultivate a deep understanding of human perception and sensoriality referring to multiple sources. With the intention to empower the ability of objects and spaces to contribute to the broadest necessities of human – social and sensorial – being, we focus attention on the invisible atmosphere that surrounds objects and evoke specific feelings. We call this holistic studio practice as ‘Culture of Creation’.

AB: We need to move away from the notion that industry is ghettoized & polluting- Industry is about organization, development & craft. At AD, there has been a conscious attempt to bridge the gap between the craft of Indian sensibility and global design. This is something I find that is similar in your work as well. Is it conscious or has it happened organically? What is your approach to this progression in your work?

SP: Indeed there are reasons why industry is ghettoized, especially heavy industry for obvious reasons. There is lot of lip service from both sides of the arguments but pollution is a real issue with many types of industries even today continuing to pollute. Especially heavy industry as well as any form of mass manufacturing ought to change or else it will become obsolete.

There has often been projection that industry is the opposite of crafts. In fact without crafts there is no industry and vice versa. In the same manner one cannot divorce making and thinking. We do not see industry and craft as separate entities, or different from each other, they are two facets of the same entity. So for us the creation is a holistic act of unity where all facets become one. While we feel that industrial manufacturing ought to be seen as a cultural act, there are very few industries around the world with that kind of awareness.