“The more abstract a visual sign is, the truer and more effective it is. An image fulfills its purpose all the more if it reaches the boundary of all form, and allows the step into the realm beyond all form. (…) Beyond all images, even the most sublime ones, there is always one more step”.

Seckel Dietrich, Before and Beyond the Image, 2004

How art and its forms have an effect on our mind and perception of the visible world is a mystery which has interested the production of artifacts since ancient times. The figurative art has searched for a correspondence between the visible and invisible world by representing the reality as seen by the eyes: a way to have access to the essence of things by means of the reproduction of their likeness. On the other side, abstractness has showed throughout history, under different guises, the unlimited possibilities of interpreting the visible reality and offering various ways to read, as well as experience, an object. Abstract images have represented the complexity of being in the world through a single act of creation without using the main subject figure, often producing works of peculiar emotional impact. Their meanings derive from what they suggest and not from what they represent. Applied symbols become a set of signs and hints which do not have a specific code, rather they offer a huge possibility of opened analogies.

As stated by Sperber Dan in his Rethinking Symbolism (1975), “It is not necessary that symbols symbolize something. There is any list given or rules generated for the interpretation of symbols. (…) None explicit shared knowledge (implicit or explicit) allows the precise and unique attribution to each symbols of its interpretations, or to each interpretation of symbols. (…) Symbol is the object of special knowledge, sometimes easily accessible, sometimes reserved to experts, sometimes forgotten today but having persisted throughout the past”. John Dewey suggested in his Art as Experience (1934) that work of art owns meanings which fall outside the world of codes and conventions of interpretations. It excludes external meanings which live outside the work of art itself: “the work of art has the unique quality, but that it is that of clarifying and concentrating meanings contained in scattered and weakened ways in the material of other experiences.”

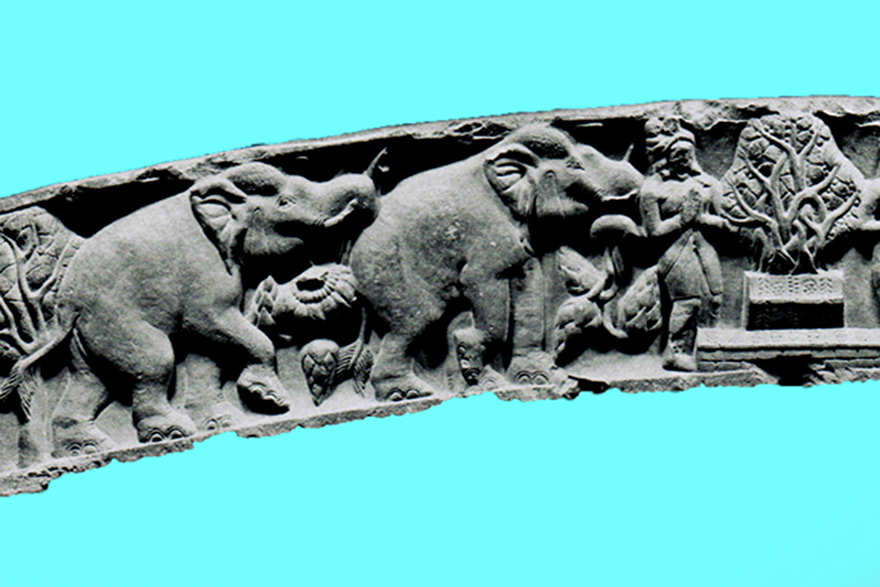

Early Indian artists had been masters of creating plentiful secular images, i.e. strong symbolic structures rooted in the world of experience, without representing the main subject of contemplation. They pushed forms beyond their evident meaning. Different forms of plant, animal and human life have been joined in a harmonious imagery without replicating the reality of the material world. The figurative guise of reliefs is accompanied by a strong abstractness rooted in the articulation of symbols, which becomes signs addressed to the legibility of images. The humanistic approach to life and social-cultural history of India then is the solid ground on which artists built their imagery. Humanistic principles of equality, consideration of life, appreciation of all human sensorial qualities, and acknowledgment of the complexity of human senses and their interaction with human intellectual, physical and emotional aptitudes, are all ingredients of aniconic depictions still today observable in panels and reliefs at Indian ancient architectural sites such as Sanchi, Ajanta and Bharhut.

The result is a celebration of life without focusing on individuals. Hence, the depiction of women and men is not addressed to the individual in itself, rather it is a part of the entire symbolic structure with its numerous attached meanings. The use of figures, such as tree, wheel, footprint, elephant etc., changes its set of associated analogies according to signs and hints of the hosting imagery context. Indeed, in early Indian art, it is not important what symbols mean but how do they mean. Then the entire imagery created comes before single figures and symbols: like in ancient Indian sculpture, where all units of forms are never recognizable in their own identity. Form, as efficiently presented by Seckel, “allows the step into the realm beyond all form”. Forms acquire a poetical significance coming from the many analogical associations offered by images. It could be affirmed, that images are offered to the spectator in a poetic context built on analogies and metaphors, arising universal responses due to the act of self-identification with the form perceived. Forms evoke past memories and instinctive associations working on the innate human aptitude to think through analogies. The essentiality and abstractness of forms further contribute to the legibility of the object, which immediately looks as familiar.

Symbols, or better signs applied in arts, are recognizable as a source of cognitive but also perceptual and sensitive knowledge. Indeed, as in any symbolic structure, the moment of interpretation is fundamental for the existence of the symbol itself. This process is not merely cognitive, but it involves all senses. Even the experience of the object contributes to the process of interpretation. All objects are built on an underlying tacit knowledge, which comes from the expressiveness of the object itself and imagery produced. Then, as taught by Indian secular art, any object and form of artifact can become more than an efficient answer to the function it offers. It can nurture our senses and mind by stimulating our innate aptitude to react to the perception of the surrounding world through the construction of analogies and meaningful associations.

“I believe that one of the most important ingredients in the method of the Indian artist, what I call the “poetic analogy” of form, has a general application to the psychological or semantic principles of sculpture the world over.”

Philips Rawson, The Methods of Indian Sculpture, 1958

Tiziana Proietti (1983, Rome, Italy) An architect with a Ph.D. In Architectural Design, Tiziana Proietti gained her doctorate at the Sapienza University of Rome in collaboration with the University of Technology TU Delft in 2013 and is currently Professor at the University of Oklahoma, USA. Her research activity explores human perception in architectural spaces with a special focus on the relationship between the senses and the cognitive value of proportion. After a decade of studies on proportion in architecture, Proietti is currently developing her research by connecting neuroscience and architecture in collaboration with the Salk Institute in San Diego and the SPaCE Lab at the University of Southern California. In 2013 she worked as a researcher at Satyendra Pakhalé Associates where she cultivated her interest in the historical and theoretical roots of sensorial design.

(1) Seckel Dietrich, Before and Beyond the Image, Artibus Asiae, Zurich 2004, pp. 56-57.

(2) Sperber Dan, Rethinking Symbolism, Cambridge Studies in Anthropology, Cambridge University Press, 1975

(3) John Dewey, Art as experience, Perigee Books, New York, 1934

(4) Philips Rawson, The Methods of Indian Sculpture, Oriental Art (1958), pp. 157